When you get into fashion, you never fully leave. The love of the fabrics is like a drug.

Isabelle de Borchgrave

"Madame de Pompadour dress," 2001, detail

Clothing Personified

There is nothing quite so personal as one’s clothing. It offers comfort, provides protection, and acts as an identifier. Worn literally next to the skin, it cools us in the morning when we put it on, and retains our heat every evening when removed. We are clothed immediately after birth, and we take our clothing with us to the grave. A shared human experience, it is unsurprising that we find ourselves particularly fascinated with the clothing of those who lived before us, be it through photographs, paintings, statues, and those articles that have survived decades and even centuries, to be viewed behind glass by curious and wondering eyes.

While interesting and important in their own right, each comes with a set of limitations. Photographs and paintings are two-dimensional, and early photography is often untinted. Unlike photographs, statues have dimension, but can be difficult to access in situ, and often have suffered damage from exposure to the elements. Surviving articles of clothing are the trickiest yet: they are extremely temperamental, easily susceptible to damage from light, air, dust, and pests. Clothing and textiles cannot be displayed for extended amounts of time, and when they are, must be kept sufficiently partitioned off from their surroundings, including the public. Furthermore, most costume collections are unable to travel, (if they do, it is at a very great cost of time and money), limiting viewership to those able to journey to them during the brief period in which they are displayed.

In this light, the work of Isabelle de Borchgrave is a stunning revelation, surmounting these inherent limitations and stepping out of the art and costume collections of museums and institutions around the world in colorful accouterments fashioned from paper.

“Empress Eugenie Evening Dress and Shoe,” 2001, after Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s ‘Madame Moitessier,’ 1856

“Empress Eugenie Evening Dress and Shoe,” 2001, after Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s ‘Madame Moitessier,’ 1856

The Artist: Isabelle de Borchgrave

Born in 1946 in Brussels, Belgium, Isabelle’s artistic talent was apparent even at a young age. One such event, in August of 1956, has stayed with her throughout the years: On the beach at Golfe-Juan, France, ten-year-old Isabelle was drawing in the sand when the artist Pablo Picasso walked by. “Picasso enjoyed watching me draw in the sand,” she recalled. She believes that moment of meeting with Picasso defined her ideas about art and being an artist. Quitting traditional school at fourteen, Isabelle attended the Centre des Arts Decoratifs and the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Her own studio was established in 1964, where she took on a variety of work to support herself, including painting designs on textiles and sewing them into dresses.

1989’s Revolution in Fashion, an exhibition catalog put out by the Kyoto Costume Institute of Japan that featured exceptional costumes and textiles from the eighteenth- and nineteenth-centuries, proved a catalyst for the paper dresses Isabelle is famous for. While in New York City, she met with long-time acquaintance Rita Brown, a costume maker for the theater. Through Brown, she met with Martin Kamer, a costume and textile dealer, who had contributed both academic work and items from his personal collection to Revolution in Fashion. Inspired, Isabelle and Rita visited The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, where they decided to do their own history of fashion, only in paper. This collaboration resulted in the original twenty-five dresses that made up their first exhibition, Papiers à la Mode. Other exhibits followed, including The World of Mariano Fortuny, The Splendor of the Medici, and Les Ballets Russes.

All four were represented in Isabelle de Borchgrave: Fashioning Art from Paper, one of the largest and most extensive displays of her work ever put on. A collaborative effort by five American institutions, the exhibit traveled to each, creating greater viewership opportunities for more people to enjoy her work. Opening in the fall of 2017 at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, Tennessee, the exhibit first traveled to the Society of the Four Arts in Palm Beach, Florida, then to the Oklahoma City Museum of Art in June 2018, followed by the Frick Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. Its final stop was in Naples, Florida, at Artis — Naples, The Baker Museum, ending 5 May 2019.

Fashioning Art From Paper at the Frick Pittsburgh

In November of 2018, I made the 2.5-hour drive from Cleveland, Ohio to the Frick Pittsburgh, located on the former estate of the Frick family on the city’s east side. The estate consists of a cluster of buildings, including a greenhouse, playhouse, café, museums, and Clayton, the family home from 1882–1905. The majority of Isabelle’s work was located in the Frick Art Museum, opened in 1970 for Helen Clay Frick’s collection of fine and decorative art. Displayed among related objects from the collection in the Italian Renaissance-style museum, itself designed to be an intimate atmosphere, the costumes are especially striking.

We begin in the rounded atrium of the Frick Art Museum, where visitors are introduced to the colorful world of Isabelle’s paper creations using whimsical costumes after Les Ballets Russes. A table, laden with papers shaped, crimped, and painted in a variety of hues, allows visitors to get a literal feel for what the objects are made of. The sculpted garments themselves are, of course, off limits.

The atrium, from left to right: “Chinese Conjurer,” 2009, after a costume by Pablo Picasso for ‘Parade’ (1917); “Paysanne,” 2009, after a costume by Mikhail Larionov for ‘Midnight Sun’ (1915); and “Le Cheval de Mer (Sea horse),” 2010, based on costumes designed by Natalia Gontcharova for ‘Sadko’ (1911)

The atrium, from left to right: “Chinese Conjurer,” 2009, after a costume by Pablo Picasso for ‘Parade’ (1917); “Paysanne,” 2009, after a costume by Mikhail Larionov for ‘Midnight Sun’ (1915); and “Le Cheval de Mer (Sea horse),” 2010, based on costumes designed by Natalia Gontcharova for ‘Sadko’ (1911)

“The Black King,” 2009, after a costume by Léon Bakst for ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ (1921)

“The Black King,” 2009, after a costume by Léon Bakst for ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ (1921)

"You Can Touch This."

"You Can Touch This."

The Kaftans

Throughout the various display areas are a series of kaftans, a type of robe or tunic worn by many cultures for thousands of years. Isabelle’s affinity for Central Asian textiles began while visiting Istanbul. In 2004, she was invited to work with Saeed Sadraee on a catalog featuring items from his extensive collection of Central Asian textiles. Isabelle chose ten textiles, re-imagining and reworking them into paper kaftans. Like the other pieces in her repertoire, the kaftans are not mere copies; instead, their design is the result of extensive research into the textiles and the techniques used to make them, which is then translated into Isabelle’s interpretation of the original.

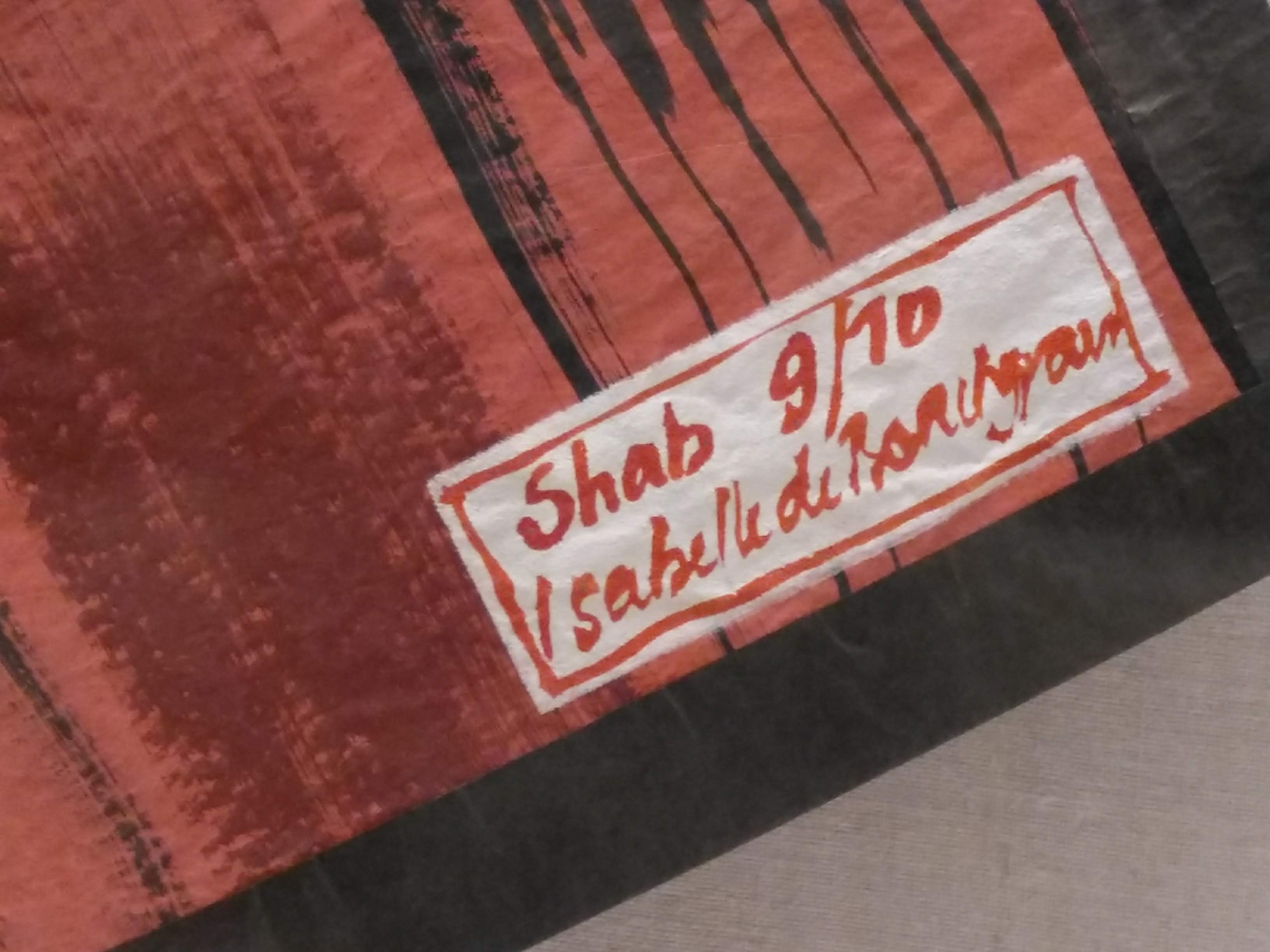

“Kaftan Shab — the Night,” 2004

“Kaftan Shab — the Night,” 2004

“Shab” is based off of the Suzani textile tradition, which are usually decorated with large-scale floral and foliage patterns done in colorful embroidery. Isabelle also worked with Ikat textiles, known for a complicated dyeing and weaving technique, with a resulting ‘blurring’ of the pattern.

“Shab” is based off of the Suzani textile tradition, which are usually decorated with large-scale floral and foliage patterns done in colorful embroidery. Isabelle also worked with Ikat textiles, known for a complicated dyeing and weaving technique, with a resulting ‘blurring’ of the pattern.

Going through the exhibit, the idea of each piece being an interpretation instead of an exact replica wasn’t always immediately noticeable. However, as many of the paper fashions were displayed with images of the originals, Isabelle’s idea of creating them “in the spirit” instead of as exact copies becomes apparent.

The Splendor of the Medici

Three such examples hail from Isabelle’s The Splendor of the Medici, arranged in a particularly Italian-feeling room, its walls adorned with paintings of religious iconography, triptychs, and cases of statuary stationed across the middle of the tile floor. Against the backdrop of the fireplace is Lorenzo il Magnifico, 2007, after Benozzo Gozzoli’s painting Procession of the Magi (1459–61), located in the Medici Chapel in Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence. Several steps away are Flora and Pallas, both taken from works by Sandro Boticelli.

“Lorenzo il Magnifico,” 2007. The appearance of short costume in the mid-fourteenth century heralded both the beginnings of fashion (as opposed to mere changing of styles) and the first movements towards modern clothing away from the long, flowing costumes inherited from the ancient world. Italy brought the open-fronted, buttoned-down costume to the rest of Europe via Greeks driven from Constantinople, examples of which are found throughout Benozzo’s “Procession of the Magi.”

“Lorenzo il Magnifico,” 2007. The appearance of short costume in the mid-fourteenth century heralded both the beginnings of fashion (as opposed to mere changing of styles) and the first movements towards modern clothing away from the long, flowing costumes inherited from the ancient world. Italy brought the open-fronted, buttoned-down costume to the rest of Europe via Greeks driven from Constantinople, examples of which are found throughout Benozzo’s “Procession of the Magi.”

“Lorenzo il Magnifico,” detail. While the scallops are three dimensional, the gemstones and pearls are painted using trompe l’oeil (French: “deceive the eye”), a technique highly favored by Isabelle and found throughout the exhibit.

“Lorenzo il Magnifico,” detail. While the scallops are three dimensional, the gemstones and pearls are painted using trompe l’oeil (French: “deceive the eye”), a technique highly favored by Isabelle and found throughout the exhibit.

Detail from Benozzo Gozzoli’s “Procession of the Magi,” thought to show Lorenzo as the youngest Magis, Caspar, though there is debate as to whether the not-yet ten-year-old would have been portrayed in such a prominent position. In either case, the stylized costume Caspar wears is particularly fine, featuring lavish textiles of silk brocade and cloth of gold, and accented with pearls and gemstones.

Detail from Benozzo Gozzoli’s “Procession of the Magi,” thought to show Lorenzo as the youngest Magis, Caspar, though there is debate as to whether the not-yet ten-year-old would have been portrayed in such a prominent position. In either case, the stylized costume Caspar wears is particularly fine, featuring lavish textiles of silk brocade and cloth of gold, and accented with pearls and gemstones.

The attire of Botticelli’s Flora (left) and Pallas (right) are much more fanciful, representing an ethereal interpretation based in Classical mythology rather than a historical time or place.

The attire of Botticelli’s Flora (left) and Pallas (right) are much more fanciful, representing an ethereal interpretation based in Classical mythology rather than a historical time or place.

“Flora,” 2007, from Sandro Botticelli’s “Primavera” (ca. 1478) (below)

“Flora,” 2007, from Sandro Botticelli’s “Primavera” (ca. 1478) (below)

“Pallas,” 2007, from Sandro Botticelli’s “Pallas and the Centaur,” (ca. 1482) (below). The work was commissioned by the Medici and hung in their Florentine palace in the same room as “Primavera”.

“Pallas,” 2007, from Sandro Botticelli’s “Pallas and the Centaur,” (ca. 1482) (below). The work was commissioned by the Medici and hung in their Florentine palace in the same room as “Primavera”.

While these three costumes likely never existed outside of their picture frames until Isabelle crafted them from paper, in an adjoining room is a costume not only seen on its sitter but is also extant itself: the Margaret Layton jacket, part of Papiers à la Mode. Made in England between 1610–15 from linen and embroidered in colored silk in patterns of fruit, flowers and insects, it was fastened with silk ribbons, of which fragments remain. In 1620 the silver-gilt bobbin lace was added to the edges.

Jacket, maker unknown, part of the V&A collection

Jacket, maker unknown, part of the V&A collection

Thought to be by Marcus Gheeraerts, the “Portrait of Margaret Layton” was painted around 1620. By this time the fashions had shifted and high-waisted styles were favored. Margaret has conformed to this new trend by hiding the lines of her unfashionably long jacket under her red silk petticoat and opaque apron, which she has pulled up to her natural waist.

Thought to be by Marcus Gheeraerts, the “Portrait of Margaret Layton” was painted around 1620. By this time the fashions had shifted and high-waisted styles were favored. Margaret has conformed to this new trend by hiding the lines of her unfashionably long jacket under her red silk petticoat and opaque apron, which she has pulled up to her natural waist.

Isabelle’s interpretation, the “Margaret Layton jacket,” 1998, seen on display with accessories.

Isabelle’s interpretation, the “Margaret Layton jacket,” 1998, seen on display with accessories.

Isabelle has added the ribbon closures while forgoing the bobbin lace on the front closure, cuffs, and bottom. A simplified version is present, however, on the collar and shoulders.

Isabelle has added the ribbon closures while forgoing the bobbin lace on the front closure, cuffs, and bottom. A simplified version is present, however, on the collar and shoulders.

Near the Margaret Layton jacket stood two paper dresses from Papiers à la Mode whose original fabric garments are also extant. Like the jacket, both were made in England, albeit over two hundred years later during the nineteenth century.

“English Dress,” 1994, after a dress from ca. 1829–31 located in the Snowshill Manor Collection of the National Trust, England.

“English Dress,” 1994, after a dress from ca. 1829–31 located in the Snowshill Manor Collection of the National Trust, England.

Detail, highlighting the replicated striped and printed cotton dress and transparent over-sleeve, the originals of which are net embroidered.

Detail, highlighting the replicated striped and printed cotton dress and transparent over-sleeve, the originals of which are net embroidered.

“English Sporting Dress and Hat,” 1992

“English Sporting Dress and Hat,” 1992

The V&A’s "Dress," ca. 1872, made from cotton and trimmed with silk braid and bone buttons. It’s ankle-length hem was most practical for walking outdoors, likely seaside or on a boat. While made of cotton for easy cleaning, it nonetheless retains elements for the fashion-conscious, with a pointed overskirt in front and a bustle in back.

The V&A’s "Dress," ca. 1872, made from cotton and trimmed with silk braid and bone buttons. It’s ankle-length hem was most practical for walking outdoors, likely seaside or on a boat. While made of cotton for easy cleaning, it nonetheless retains elements for the fashion-conscious, with a pointed overskirt in front and a bustle in back.

After these traditional art galleries of the Frick Art Museum, Fashioning Art From Paper continues into a more contemporary display space, presumably used by the Frick for special exhibits. In these rooms the displays morph into a classic “costume museum” layout (minus the glass cases) in which the paper sculptures are loosely arranged according to original exhibit, genre, and time period.

First up: A harmonious coupling of Les Ballets Russes and The World of Mariano Fortuny.

Les Ballets Russes

From ‘Les Ballets Russes,’ from front to back: “The Blue God,” 2009; “Attendant of Kostechei the Immortal,” 2009; “Fish with Red Peas,” 2010; “Male Guest,” 2009

From ‘Les Ballets Russes,’ from front to back: “The Blue God,” 2009; “Attendant of Kostechei the Immortal,” 2009; “Fish with Red Peas,” 2010; “Male Guest,” 2009

Les Ballets Russes is a merry explosion of bright, poppy colors splashed across the fanciful costumes of the famed dance troupe. First performing at the Theatre du Chatelet in May 1909, the Ballets Russes “redefined” ballet for the next century through utilization of new choreography, music, and stars. From 1909 to 1929, the dancers and choreographers of the Ballets Russes, led by Sergei Diaghilev, reinvented classical Ballet by introducing modernity and artistic expression to the once-stagnant art form. The Ballets’ collaboration with contemporary artists such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, combined with a daring use of color, proved attractive for Isabelle. “I always loved the combination of poverty and the riches of the Ballets Russes,” she explained. “Costumes were made of all types of materials including burlap potato sacks painted and dyed in bold colors.” While some of the actual costumes survive, Isabelle prefers working off of photographs and artist’s drawings, focusing on the overall creative expression that they originally brought to the stage rather than those pieces favored by museums.

(Left to right) Tutu 2, 1, 3, 2008

(Left to right) Tutu 2, 1, 3, 2008

“The Woman in Blue,” 2009, after a costume by Pablo Picasso in “Le Tricorne” (1919). The ballet is based on a nineteenth-century story set in an eighteenth-century Spanish village. Picasso’s design combines his use of cubism with traditional Spanish motifs of bullfights, boleros, and mantillas, and was considered a triumph of modernism.

“The Woman in Blue,” 2009, after a costume by Pablo Picasso in “Le Tricorne” (1919). The ballet is based on a nineteenth-century story set in an eighteenth-century Spanish village. Picasso’s design combines his use of cubism with traditional Spanish motifs of bullfights, boleros, and mantillas, and was considered a triumph of modernism.

(Left to right) “Mandarin,” 2009; “Lady of the Court,” 2009; “Mourner,” 2009. All are after costumes designed by Henri Matisse for “The Song of the the Nightingale” (1920). Matisse based his designs on traditional Chinese court dress and ceramics.

(Left to right) “Mandarin,” 2009; “Lady of the Court,” 2009; “Mourner,” 2009. All are after costumes designed by Henri Matisse for “The Song of the the Nightingale” (1920). Matisse based his designs on traditional Chinese court dress and ceramics.

Across from the brilliant specimens of Les Ballets Russes are the equally dazzling, elegant forms of The World of Mariano Fortuny.

The World of Mariano Fortuny

A selection of sculptures after the Fortuny Delphos dress; note Kaftan “Bahar (Spring),” 2004, on the far wall.

A selection of sculptures after the Fortuny Delphos dress; note Kaftan “Bahar (Spring),” 2004, on the far wall.

Born in Granada, Mariano Fortuny (1871–1949) moved to Venice with his mother in 1889. His father, Spanish genre painter Mariano Fortuny, had died in 1874. A trained painter himself, Fortuny’s work grew to include set design and stage lighting, where he fully embraced the Wagnerian idea of Gesamtkunstwerk (German: “total work of art”) by seeking to create the perfect union of music, drama, and visual presentation. While his innovative designs spread throughout the theaters and aristocratic homes of Europe during the first decades of the twentieth century, he once again expanded his creative genius, this time into the world of high fashion. Creating fabrics and printed textiles, he and his wife, Henriette Nigrin (m. 1924), constructed the Delphos, a plissé silk dress based off of the ancient Greek peplos, that catapulted him to international fame.

“Delphos Dress and Shawl,” 2006–7, with printed belt and shawl. The bead trim is modeled after those by Venetian glass house Murano. Along the wall behind the dresses are images of Isabelle’s ensembles on display at the Palazzo Fortuny, in 2008’s exhibit ‘A World of Paper: Isabelle de Borchgrave Encounters Mariano Fortuny.’

“Delphos Dress and Shawl,” 2006–7, with printed belt and shawl. The bead trim is modeled after those by Venetian glass house Murano. Along the wall behind the dresses are images of Isabelle’s ensembles on display at the Palazzo Fortuny, in 2008’s exhibit ‘A World of Paper: Isabelle de Borchgrave Encounters Mariano Fortuny.’

Long closed to visitors, the Palazzo Fortuny was a constant draw for Isabelle on her many visits to Venice. In fact, she would often go up and knock on the front door, hoping to be let inside. Her work of paper dresses already included a Fortuny, and having an exhibition at the Palazzo was an ambitious fantasy. Her wishes came true in 2008, after the Palazzo’s 2001 reopening to the public prompted collaborations with guest artists. A World of Paper: Isabelle de Borchgrave Encounters Mariano Fortuny was installed on three floors of the Palazzo, with her work being displayed in Fortuny’s fabric-covered rooms next to his original paintings, theater works, and lighting instruments, as well as a reconstruction of Isabelle’s studio.

“Silk Velvet Burnous,” 2008 (left) and “Delphos Dress with Knossos Shawl,” 2008. The Burnous is modeled after Fortuny’s theater costumes, which he based on a combination of Italian Renaissance and Middle-Eastern influences, while the Delphos comes from the ancient Greek bronze statue, the “Charioteer of Delphi,” known for it’s finely pleated chiton.

“Silk Velvet Burnous,” 2008 (left) and “Delphos Dress with Knossos Shawl,” 2008. The Burnous is modeled after Fortuny’s theater costumes, which he based on a combination of Italian Renaissance and Middle-Eastern influences, while the Delphos comes from the ancient Greek bronze statue, the “Charioteer of Delphi,” known for it’s finely pleated chiton.

“Delphos Dress with Knossos Shawl,” detail. Fortuny was secretive about his method for achieving the fine pleats seen in the Delphos dresses. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, in all likelihood the panels of silk were loosely hand-stitched back and forth across the fabric. At the end of the panel, the thread was pulled tight to create a narrow piece of cloth that was then sent through heated ceramic rollers. As this process did not permanently set the pleats, any pleats flattened from sitting or accidentally wetting them meant Fortuny’s customers had to return their dresses to his studio to have the pleats reset.

“Delphos Dress with Knossos Shawl,” detail. Fortuny was secretive about his method for achieving the fine pleats seen in the Delphos dresses. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, in all likelihood the panels of silk were loosely hand-stitched back and forth across the fabric. At the end of the panel, the thread was pulled tight to create a narrow piece of cloth that was then sent through heated ceramic rollers. As this process did not permanently set the pleats, any pleats flattened from sitting or accidentally wetting them meant Fortuny’s customers had to return their dresses to his studio to have the pleats reset.

***The Splendor of the Medici ***

Moving on into the next display space sends us back into the fifteenth century with more selections from 2009’s Splendor of the Medici, whose original debut took place at the Palazzo Medici Riccardi alongside the original paintings.

The Medici’s first came to Florence around the twelfth century, rising to prominence through banking and commerce. In 1434, Cosimo the Elder (1389–1464) became the chief political leader of Florence, ruling the city as its uncrowned king until his death. Both Cosimo and his grandson, Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449–1492) were outstanding patrons of the arts, patronizing the likes of Donatello, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo. While Lorenzo’s elder son Piero was an ineffectual ruler, being exiled from Florence in 1494, his younger son Giovanni (the future Pope Leo X) was able to negotiate the Medici’s return in 1512. The family regained power, eventually sending Catherine de Medici (1519–1589) to France as the wife of Henry II.

By 1537 the rule of Cosimo the Elder’s descendants came to an end with the assassination of Alessandro de’ Medici, and the descendants of his brother, Lorenzo the Elder, took the reins. Lorenzo’s great-great-grandson, Cosimo I (1519–1574) became duke of Florence in 1537, then grand duke of Tuscany in 1569. His descendants would rule with absolute power until 1737, when Gian Gastone, the last Medici grand duke, died without a male heir.

In Splendor of the Medici, Isabelle captures the sumptuousness of the clothing worn by key members of the family, whose centuries-spanning saga is filled with tales of love and lust, power and purgatory, money and murder.

(Right to left) “Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–1574),” 2007, portrayed in his coronation robes as Grand Duke, after a ca. 1600–03 portrait by Ludovico Cardi; “Bianca (Bia) de’ Medici (ca. 1536–1542),” 2006, after a posthumous portrait by Agnolo Bronzino. Bia was the daughter of Cosimo I, born prior to his marriage with Eleanor of Toledo in 1539; “Eleanor of Toledo (1522–1562),” 2007, wife of Cosimo I; “Maria de’ Medici (1540–1557),” 2007, daughter of Cosimo I and Eleanor of Toledo; “Marie de’ Medici (1575–1642),” 2006, granddaughter of Cosimo I and Eleanor of Toledo.

(Right to left) “Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–1574),” 2007, portrayed in his coronation robes as Grand Duke, after a ca. 1600–03 portrait by Ludovico Cardi; “Bianca (Bia) de’ Medici (ca. 1536–1542),” 2006, after a posthumous portrait by Agnolo Bronzino. Bia was the daughter of Cosimo I, born prior to his marriage with Eleanor of Toledo in 1539; “Eleanor of Toledo (1522–1562),” 2007, wife of Cosimo I; “Maria de’ Medici (1540–1557),” 2007, daughter of Cosimo I and Eleanor of Toledo; “Marie de’ Medici (1575–1642),” 2006, granddaughter of Cosimo I and Eleanor of Toledo.

For most of Western costume history, all but the very youngest children wore scaled-down versions of their parent’s clothes. From left: “Anna de’ Medici (1616–1676),” 2006, after Justus Sustermans’ 1622 portrait of her, when she was about six years old; “Leopoldo de’ Medici in Polish Dress (1617–1675),” 2006, inspired by Susterman’s “Portrait of Leopoldo de’ Medici at four years of age;” “Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici (1611–1663),” 2007, after Susterman’s “Portrait of Giovan Carlo de’ Medici at ten years of age.”

For most of Western costume history, all but the very youngest children wore scaled-down versions of their parent’s clothes. From left: “Anna de’ Medici (1616–1676),” 2006, after Justus Sustermans’ 1622 portrait of her, when she was about six years old; “Leopoldo de’ Medici in Polish Dress (1617–1675),” 2006, inspired by Susterman’s “Portrait of Leopoldo de’ Medici at four years of age;” “Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici (1611–1663),” 2007, after Susterman’s “Portrait of Giovan Carlo de’ Medici at ten years of age.”

According to Isabelle, the Medici’s are the most complicated ensembles she had created so far. In addition to the obvious lavishness of the clothing itself, there was the need to translate the seated individuals in the portraits into standing paper ones. To achieve this, she worked with ten assistants for over a year, creating thirty costumes complete with jewelry, shoes, and accessories. Trompe l’oeil is heavily utilized; one dress features 4,000 hand-painted pearls in this method.

“Maria de’ Medici (1540–1557),” 2007, after Alessandro Allori’s ‘Portrait of Maria de Medici’ (ca. 1555). Maria’s clothing reflects the influence of Spanish fashions on Italian dress, featuring a blue outer gown and embroidered under gown. Her long sleeves are fitted, with rolled epaulettes. As befits her social status, Maria is laden with ornaments, from her pearl necklace, jeweled girdle, chain, and headpiece, to the ring on her finger and gloves in her hand: all point to her rank and wealth.

“Maria de’ Medici (1540–1557),” 2007, after Alessandro Allori’s ‘Portrait of Maria de Medici’ (ca. 1555). Maria’s clothing reflects the influence of Spanish fashions on Italian dress, featuring a blue outer gown and embroidered under gown. Her long sleeves are fitted, with rolled epaulettes. As befits her social status, Maria is laden with ornaments, from her pearl necklace, jeweled girdle, chain, and headpiece, to the ring on her finger and gloves in her hand: all point to her rank and wealth.

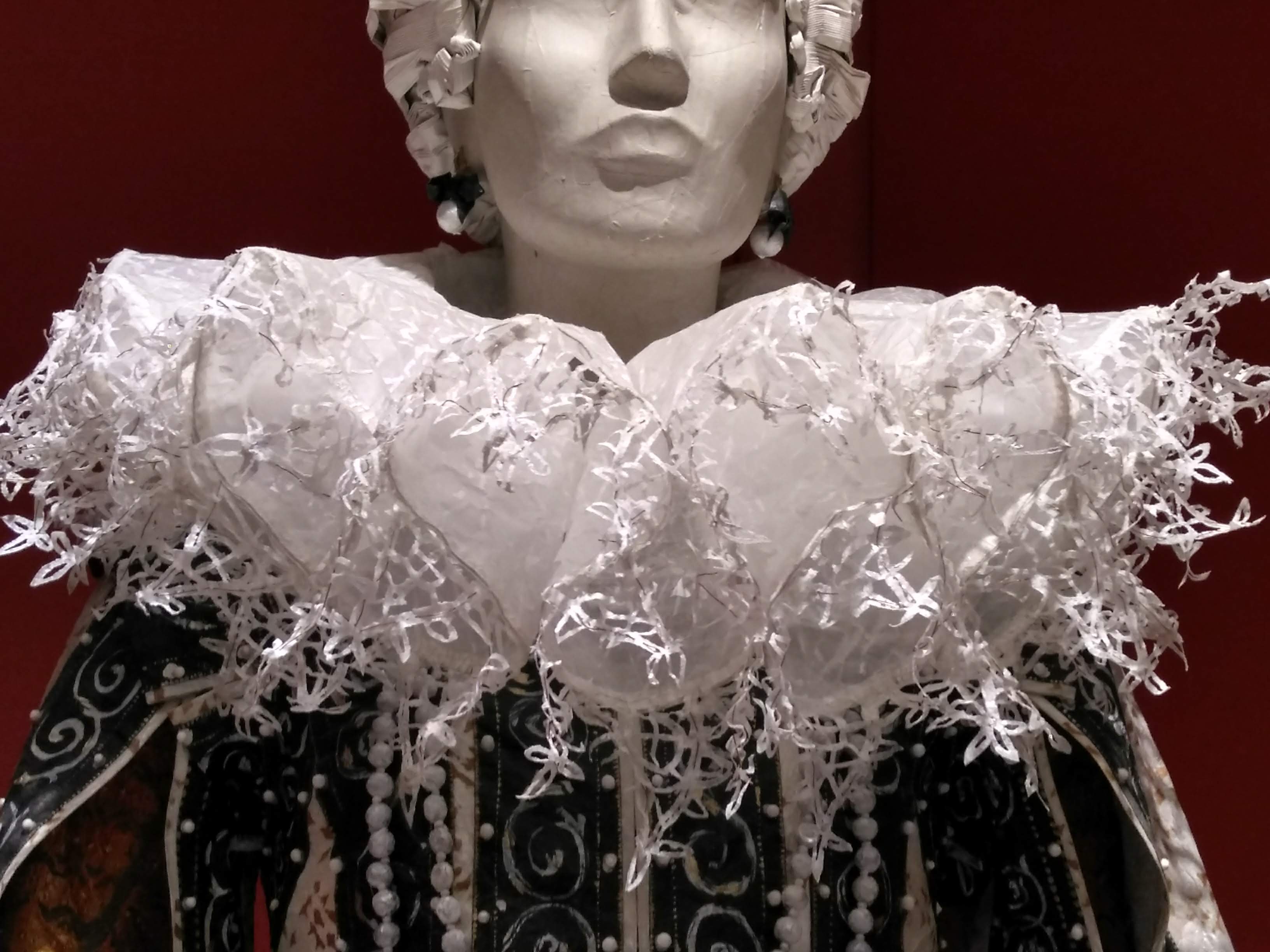

“Marie de’ Medici (1575–1642),” 2006, after ‘Marie de Medici’ (1595) by Pietro Facchietti. The granddaughter of Eleanor of Toledo and Cosimo I, Marie married King Henri IV of France (1553–1610) in October of 1600 at the age of twenty. The unhappy marriage ended with Henri’s assassination on 14 May 1610, a day after her coronation, after which she served as regent for her son, King Louis XIII. Never a shrewd politician, she endured several bouts of exile, spending the last eleven years of her life outside of France.

“Marie de’ Medici (1575–1642),” 2006, after ‘Marie de Medici’ (1595) by Pietro Facchietti. The granddaughter of Eleanor of Toledo and Cosimo I, Marie married King Henri IV of France (1553–1610) in October of 1600 at the age of twenty. The unhappy marriage ended with Henri’s assassination on 14 May 1610, a day after her coronation, after which she served as regent for her son, King Louis XIII. Never a shrewd politician, she endured several bouts of exile, spending the last eleven years of her life outside of France.

“Marie de’ Medici,” detail. Due to their appearance in portraits of her, the fabulous ruffs worn by Marie later came to be known as the Medici collar. As it dates from twenty years prior to her reign, this characterization is inaccurate.

“Marie de’ Medici,” detail. Due to their appearance in portraits of her, the fabulous ruffs worn by Marie later came to be known as the Medici collar. As it dates from twenty years prior to her reign, this characterization is inaccurate.

Featured among the assembly of Medici is Charlotte-Marguerite de Montmorency, Princess of Condé, commissioned by the Frick Pittsburgh specifically for Fashioning Art from Paper. Modeled after the museum’s 1609 portrait of the sixteen-year-old Princess by Peter Paul Rubens, both the dress and the portrait were permitted to travel to the other four locations as part of the exhibit.

Peter Paul Rubens, “Portrait of Charlotte-Marguerite de Montmorency, Princess of Condé” (ca. 1609). This portrait was likely painted by Rubens at the Brussels court, where the newly-married Princess had arrived with her husband after fleeing the advances of the lecherous Henri IV, King of France and husband of Marie de’ Medici.

Peter Paul Rubens, “Portrait of Charlotte-Marguerite de Montmorency, Princess of Condé” (ca. 1609). This portrait was likely painted by Rubens at the Brussels court, where the newly-married Princess had arrived with her husband after fleeing the advances of the lecherous Henri IV, King of France and husband of Marie de’ Medici.

While unsigned, the Frick has two indicators that the portrait was painted by Rubens: first, the style of painting the Princess’s hands, which are delicate and have cool blue undertones, is conventional Rubens. Second, documentary evidence links an old inventory number on the painting to one mentioned in a 1655 inventory taken of the possessions of Diego de Güzman, Marquis of Leganès, where number 326 is listed as a “Portrait of the Princess of Condé by the hand of Rubens.”

Isabelle and her team worked to capture the variety of fabrics, textures, and details worn by the Princess in her portrait, transforming plain white rolls of paper into a sculptural masterpiece of art in its own right.

“Costume of the Princess of Condé, Charlotte-Marguerite de Montmorency, (1594–1650),” 2017. Spanish influences of the previous century seen in the Medici’s are still present in the Princess’s costume, albeit with some shifts towards the softer French styles of the 1600s. The voluminous, slashed sleeves and tightly fitted bodice ending in a point remain, as does the low-cut neckline finished with a high flaring collar in lieu of a ruff.

“Costume of the Princess of Condé, Charlotte-Marguerite de Montmorency, (1594–1650),” 2017. Spanish influences of the previous century seen in the Medici’s are still present in the Princess’s costume, albeit with some shifts towards the softer French styles of the 1600s. The voluminous, slashed sleeves and tightly fitted bodice ending in a point remain, as does the low-cut neckline finished with a high flaring collar in lieu of a ruff.

“Costume of the Princess of Condé,” detail. The roll of the sixteenth-century farthingale has given way to the tray-like style seen here, lending the skirt more of a rounded drum appearance in contrast to the farthingale’s cone.

“Costume of the Princess of Condé,” detail. The roll of the sixteenth-century farthingale has given way to the tray-like style seen here, lending the skirt more of a rounded drum appearance in contrast to the farthingale’s cone.

The subtle changes in style and costume present with the Medici and Princess of Condé are made easily apparent in the final two galleries, where a plethora of fashion history is to be found in the fabulous Papiers à la Mode.

A juxtaposition of centuries

A juxtaposition of centuries

Papiers à la Mode

Papiers à la Mode was the first series of paper sculptures put on by Isabelle, in collaboration with Rita Brown. A theatrical costume maker, Rita’s knowledge of pattern making and period clothing was crucial in getting the project off the ground. By 1998, Isabelle and Rita had created twenty-five pieces that were first exhibited at the Musée de l’Impression sur Etoffes in Mulhouse, France. They went on to exhibit at more than thirty institutions around the world, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The exemplary guidebook, Isabelle de Borchgrave: Fashioning Art from Paper, eloquently sums up the experience:

Papiers à la Mode assembles a connoisseur’s selection of designs that could never be possible any other way. For fashion enthusiasts, it is a dream list from the history of dress drawn from both paintings and actual garments representing a selection of beautiful silhouettes from various periods in exquisite and unusual textiles. Importantly, they enrich our understanding of the history of dress by helping us see this selection of designs together in new ways and many for the first time in a lifelike format.

And so, in no particular order, a selection from Papiers à la Mode, as seen in the Frick Pittsburgh.

“Elizabeth I court dress,” 2001, after “Queen Elizabeth,” ca. 1599. Renowned since the Middle Ages, English embroidery reached new heights during the sixteenth century with the invention of steel needles and the importing of higher volumes of colored silks. The original painting is kept in Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, and might have been commissioned by Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury. The famous textile and needlework collection of Bess of Hardwick, as she is commonly known, is also housed in the Hall, and it is possible that the embroidery of Elizabeth’s dress was designed and worked on by Bess herself.

“Elizabeth I court dress,” 2001, after “Queen Elizabeth,” ca. 1599. Renowned since the Middle Ages, English embroidery reached new heights during the sixteenth century with the invention of steel needles and the importing of higher volumes of colored silks. The original painting is kept in Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, and might have been commissioned by Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury. The famous textile and needlework collection of Bess of Hardwick, as she is commonly known, is also housed in the Hall, and it is possible that the embroidery of Elizabeth’s dress was designed and worked on by Bess herself.

"Mantua," 2011. Isabelle has replicated through paint the abstract flowers and leaves woven into the ivory silk brocade of the original dress. As befits a court costume, the neutral whites, ivories, and browns are shot through with a healthy helping of gold. While here it is merely gold paint, the original contains actual gilt thread.

"Mantua," 2011. Isabelle has replicated through paint the abstract flowers and leaves woven into the ivory silk brocade of the original dress. As befits a court costume, the neutral whites, ivories, and browns are shot through with a healthy helping of gold. While here it is merely gold paint, the original contains actual gilt thread.

*The original Mantua, 1755–1760, held in the V&A, which I had the pleasure of viewing in person in July 2015. The fabric itself was woven between 1753–55, probably in France but possibly in London by weavers copying the styles of their compatriots across the Channel.

*

*The original Mantua, 1755–1760, held in the V&A, which I had the pleasure of viewing in person in July 2015. The fabric itself was woven between 1753–55, probably in France but possibly in London by weavers copying the styles of their compatriots across the Channel.

*

“Sarah Bernhardt ‘Gismonda’ Dress,” 1998. Originally premiering in 1894 Paris, ‘Gismonda’ starred Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923) as the title character; she was also the director. This dress is based off of a promotional poster by Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939), featuring Bernhardt in costume in the climatic final act of the play. Delighted with the result by the then-unknown Mucha, Bernhardt commissioned him to produce stage and costume designs as well as posters. After 1896 she used his posters to promote her American tour, providing him with the opportunity to expand his career in America after 1904.

“Sarah Bernhardt ‘Gismonda’ Dress,” 1998. Originally premiering in 1894 Paris, ‘Gismonda’ starred Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923) as the title character; she was also the director. This dress is based off of a promotional poster by Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939), featuring Bernhardt in costume in the climatic final act of the play. Delighted with the result by the then-unknown Mucha, Bernhardt commissioned him to produce stage and costume designs as well as posters. After 1896 she used his posters to promote her American tour, providing him with the opportunity to expand his career in America after 1904.

A collection of evening gowns inspired by Redfern, Lanvin, and Poiret, 1994–98. Modeled after dresses from the mid-1920s, Isabelle’s creations reflect post-Great War fashions: shortened skirts on tunic-style dresses, open arms and necks free of décolletage. Gone was the richness of the preceding Belle Epoch, however, a taste for the fine can still be seen in the textiles themselves, which often feature strong colors, metal brocades, and elaborate bead work and embroidery.

A collection of evening gowns inspired by Redfern, Lanvin, and Poiret, 1994–98. Modeled after dresses from the mid-1920s, Isabelle’s creations reflect post-Great War fashions: shortened skirts on tunic-style dresses, open arms and necks free of décolletage. Gone was the richness of the preceding Belle Epoch, however, a taste for the fine can still be seen in the textiles themselves, which often feature strong colors, metal brocades, and elaborate bead work and embroidery.

“Empress Eugénie Evening Dress and Shoe,” 2001. Though this ensemble is closely based on an 1856 portrait of Madame Moitessier by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Isabelle has chosen to attribute her version to the Empress Eugénie. Mme Moitessier’s dress is made of French Lyon silk, an appropriate material for the Empress. Wide crinolines, deeply cut necklines exposing the shoulders, and shawl berthas encircling the shoulders and ending in a deep point at the waist made up fashionable evening attire throughout the 1850s.

“Empress Eugénie Evening Dress and Shoe,” 2001. Though this ensemble is closely based on an 1856 portrait of Madame Moitessier by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Isabelle has chosen to attribute her version to the Empress Eugénie. Mme Moitessier’s dress is made of French Lyon silk, an appropriate material for the Empress. Wide crinolines, deeply cut necklines exposing the shoulders, and shawl berthas encircling the shoulders and ending in a deep point at the waist made up fashionable evening attire throughout the 1850s.

“Gown La Vaporeuse,” 2001, inspired by Rose Adélaïde Decreux’s ‘Self-portrait with a Harp,’ 1791. Exhibited in the Salon the last year before the fall of the French monarchy, Decreux’s elegant attire reflects her status as a young Parisian woman of taste, refinement, and accomplishment. The light, gauzy fabric seen crossed in front of the bodice of the dress is a fischu, and is similar to a shawl. This manner of wearing one’s fischu around the shoulders, crossed over the chest and tied behind one’s back was popular for the time period.

“Gown La Vaporeuse,” 2001, inspired by Rose Adélaïde Decreux’s ‘Self-portrait with a Harp,’ 1791. Exhibited in the Salon the last year before the fall of the French monarchy, Decreux’s elegant attire reflects her status as a young Parisian woman of taste, refinement, and accomplishment. The light, gauzy fabric seen crossed in front of the bodice of the dress is a fischu, and is similar to a shawl. This manner of wearing one’s fischu around the shoulders, crossed over the chest and tied behind one’s back was popular for the time period.

“Robe à la Française and Shoes,” 2010. When most people think of eighteenth-century women’s wear, the robe à la française, or French-style dress, is what comes to mind. This particular interpretation features an open petticoat and a stomacher covered by a row of ribbon bows. According to the accompanying informative sign, Isabelle used three different papers to create this ensemble: the majority of the dress is made from an inexpensive Belgian paper, like those used to wrap chocolate bars; accessories are made from a paper similar to Kraft; finally, a gauze-type paper imported from England gives life to the airy lace and veil components.

“Robe à la Française and Shoes,” 2010. When most people think of eighteenth-century women’s wear, the robe à la française, or French-style dress, is what comes to mind. This particular interpretation features an open petticoat and a stomacher covered by a row of ribbon bows. According to the accompanying informative sign, Isabelle used three different papers to create this ensemble: the majority of the dress is made from an inexpensive Belgian paper, like those used to wrap chocolate bars; accessories are made from a paper similar to Kraft; finally, a gauze-type paper imported from England gives life to the airy lace and veil components.

“Robe à la Française,” detail. In 1675, Louis XIV created a company of female dressmakers, under the opinion that it was more ‘seemly’ for women to be dressed by members of their own sex. Previously, both men and women were dressed by male tailors. By the 1770's and 1780's, the dressmakers had obtained a level of skill apparent in extant pieces, creating precisely fitted garments held together by elegant, meticulous stitches. The bow-covered stomacher acted as the front of the dress, covering the empty space left at the center after the bodice fabric had been shaped around the torso (darts would not be used until the 1800's). Divisions of labor dictated that plain false front stomachers were made by the dressmaker, while ribbon fronts, considered a trimming and a decorative feature, were made by a milliner.

“Robe à la Française,” detail. In 1675, Louis XIV created a company of female dressmakers, under the opinion that it was more ‘seemly’ for women to be dressed by members of their own sex. Previously, both men and women were dressed by male tailors. By the 1770's and 1780's, the dressmakers had obtained a level of skill apparent in extant pieces, creating precisely fitted garments held together by elegant, meticulous stitches. The bow-covered stomacher acted as the front of the dress, covering the empty space left at the center after the bodice fabric had been shaped around the torso (darts would not be used until the 1800's). Divisions of labor dictated that plain false front stomachers were made by the dressmaker, while ribbon fronts, considered a trimming and a decorative feature, were made by a milliner.

“Madame de Pompadour Court Dress,” 2001, after ‘Madame de Pompadour,’ 1756, by François Boucher. Louis XV’s mistress and fashion icon in her own right, Mme Pompadour’s emerald green robe à la française features a ladder of ribbons (échelle) across the front, layers of trim running from the neck down the open skirts and across the bottom of the petticoat, and numerous artificial flowers. Abundant ornamentation was crucial to women’s dress at the time; extant garments bear a multitude of tiny holes from the needles and pins used to secure these necessary additions.

“Madame de Pompadour Court Dress,” 2001, after ‘Madame de Pompadour,’ 1756, by François Boucher. Louis XV’s mistress and fashion icon in her own right, Mme Pompadour’s emerald green robe à la française features a ladder of ribbons (échelle) across the front, layers of trim running from the neck down the open skirts and across the bottom of the petticoat, and numerous artificial flowers. Abundant ornamentation was crucial to women’s dress at the time; extant garments bear a multitude of tiny holes from the needles and pins used to secure these necessary additions.

“Madame de Pompadour Court Dress and Shoe,” 2007, left; “Banyan and Waistcoat,” 1998, right.

“Madame de Pompadour Court Dress and Shoe,” 2007, left; “Banyan and Waistcoat,” 1998, right.

Also inspired by Mme Pompadour (after Maurice Quentin de la Tour’s ‘Jeanne Poisson (1721–64), the Marquise de Pompadour,’ 1755), this robe à la française points to her love of roses, here embroidered into the fabric of her sumptuous court gown. Although the posthumous inventory of her estate includes numerous jewels (especially diamonds), in her many portraits her use of jewelry is limited, instead the primary source of adornment is the ethereal layering of ribbons, bows, and lace.

Also inspired by Mme Pompadour (after Maurice Quentin de la Tour’s ‘Jeanne Poisson (1721–64), the Marquise de Pompadour,’ 1755), this robe à la française points to her love of roses, here embroidered into the fabric of her sumptuous court gown. Although the posthumous inventory of her estate includes numerous jewels (especially diamonds), in her many portraits her use of jewelry is limited, instead the primary source of adornment is the ethereal layering of ribbons, bows, and lace.

One of the few examples of menswear in the exhibition, this banyan and waistcoat are based off of a 1730 set belonging to Peter the Great of Russia. While this particular example is quite elaborate by modern standards, the banyan was an informal dressing gown, worn by a man in the privacy of his home. Following an increased interest in the kaftans from the Middle East and Eastern Europe, banyans became popular in the early 1700's, and remained so throughout the 1800's. With Isabelle’s own personal interest in the kaftan, it seems quite fitting that she would create such a magnificent example of the banyan for ‘Papiers à la Mode.’

One of the few examples of menswear in the exhibition, this banyan and waistcoat are based off of a 1730 set belonging to Peter the Great of Russia. While this particular example is quite elaborate by modern standards, the banyan was an informal dressing gown, worn by a man in the privacy of his home. Following an increased interest in the kaftans from the Middle East and Eastern Europe, banyans became popular in the early 1700's, and remained so throughout the 1800's. With Isabelle’s own personal interest in the kaftan, it seems quite fitting that she would create such a magnificent example of the banyan for ‘Papiers à la Mode.’

Life in Paper

The personal is found throughout Fashioning Art from Paper. Most apparent is that of Isabelle de Borshgrave herself, whose interests, tastes, and artistic talent are worked into every piece. Although seen through Isabelle’s interpretation, the designers, artists, and sitters originally behind the ensembles are represented as well, from the colorful modernity of Sergei Diaghilev’s Les Ballets Russes to the frothy confections of Madame de Pompadour’s portraits. Fashioning Art from Paper is truly special in that we are able to see shifting fashions, interests, and values across centuries and regions in the clothing worn by a variety of people. This experience is of itself highly personal, as we take in past styles and time periods that are decidedly foreign while discovering a commonality with the people themselves: The desire to take our most personal possession, our clothing, and through it display who we are to the world.

Additional sources and further reading:

Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987.

Kyoto Costume Institute. [Revolution in Fashion 1715–1815.](https://www.librarything.com/work/312357) New York: Abbeville Press, 1989.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, The. [100 Dresses](https://store.metmuseum.org/100-dresses-80007275). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010.

Sewell, Dennita. [Isabelle de Borchgrave: Fashioning Art from Paper.](https://isabelledeborchgrave.com/collections/paper-gifts/products/isabelle-de-borchgrave-fashioning-art-from-paper) Seattle: Lucia-Marquand, 2018.

![image]https://res.cloudinary.com/frannsoft/image/upload/v1585065309/blackcatwhiterabbit/fashioning-life-from-paper/blackkingdetail.jpg