Founded by Samuel Slater (1768-1835), in 1793, Slater Mill is credited with starting the Industrial Revolution in the United States.

Slater was born in Belper, Derbyshire, England.Apprenticed at the age of fourteen to Jedediah Strutt, owner of one of the first cotton mills in Belper, Slater obtained a complete understanding of the machinery used in the textile industry. When he first entered Strutt’s employ, young Slater signed an agreement promising never to reveal the plans of the machines used in the mill, to powers either domestic or foreign. However, eight years and the position of superintendent later, Slater, believing he had no future in England, secretly immigrated to the United States in 1789 disguised as a farmer, the apprenticeship papers proving his experience in the textile industry sewn into his clothing.

After arriving in New York, Slater learned of William Almy and Smith Brown, relatives and business partners of the Quaker merchant and intellectual Moses Brown, who were engaged in running a small textile mill in Pawtucket. Almy and Brown, financially backed by Moses Brown, had already purchased the necessary machinery to operate a textile mill, but their operation was plagued by the lack of a skilled manager for the machines.

Enter Samuel Slater. He became the lynchpin in this first successful water powered textile mill that today is known as Old Slater Mill. According to Paul E. Rivard, author of a short interpretive essay on Slater and his role in the beginnings of the American textile industry:

“The establishment of a successful spinning mill in Pawtucket was due to a fortunate convergence of factors: the iron and woodworking skills [of shipbuilders] of the Pawtucket area, the [spinning machine] experiments undertaken in the Pawtucket Falls area … and, finally, Samuel Slater’s arrival with his great knowledge of the entire operation of cotton textile machinery.”

Slater Mill today is a National Historic Landmark, run by the Old Slater Mill Association (OSMA). The OSMA preserves and stewards the site, and the museum celebrates innovation and the entrepreneurial spirit by engaging audiences in relevant cultural, historic, and artistic endeavors.7 The Historic Landmark known as Slater Mill consists of three buildings: the Sylvanus Brown House, the Wilkinson Mill, and Old Slater Mill. Visitors are taken on guided tours through each, beginning with the House and ending with Old Slater Mill.

We begin with the Sylvanus Brown House, built in 1758 and located behind the Mill. Originally positioned near present-day Interstate 95, the building was lifted from its foundation and transported on a flatbed truck to the site in 1962, an image of the house on the flatbed is shown on the informative sign in front. Each of the three buildings has one of these signs, so even if you don’t purchase the tour you can still walk around the structures and learn a little something about them, and the signs include referential images as well as text.

Sylvanus Brown, one of the skilled mechanics employed by Almy and Brown, lived in the house from 1784 to 1824 and his house is furnished according to Brown’s 1825 probate inventory. Upon his arrival, Slater lived in the house with Brown and his family; one of its rooms saw Slater’s initial interview with his potential employers.

The house itself is very plain and sparsely furnished. It is typical of an artisan’s home of the mid to late 1700s, containing a loom, spinning wheels, and other tools used in making cloth by hand. Ruth Brown, Sylvanus’ wife, would have made the family’s cloth until the invention of the power loom in the early 1800s. The overarching theme of this building was “Before Industrialization,” with emphasis being placed on the personal aspects of home cloth making, especially on time. It took a long time to make home cloth; for example, making one set of wool clothing from sheep to the final wearing took up to one year. In the second room, our tour guide Kathryn demonstrated weaving on a loom from the early nineteenth century.

A reconstructed lower level makes up the kitchen area of the Brown house, and a kitchen garden adds a colorful touch. In addition to the regular vegetables and flowers, Slater Mill is planning to add plants early Americans used as fabric dyes to the beds as well [as of 2016].

The stone building seen behind and to the right of the garden is the Wilkinson Mill, up next on the tour. Approaching the building, Kathryn spoke again about time. While the residents of the Sylvanus Brown House spent a lot of time working on their clothing, at the end of the day their time was their own: they worked for themselves and for their families. As farmers transitioned to factory workers, they began working for others instead, and their time was no longer their own. For example, Kathryn told of mills where workers were on the job for ten or more hours a day, six days a week, with a half an hour for lunch and one timed additional bathroom break of seven minutes per employee.

Wilkinson Mill has two floors open for viewing. Built between 1810 and 1811 by David Wilkinson (1771-1852) and his father, this “rubblestone [sic]” mill hosted a machine shop, spinning mill, and blacksmith shop. Wilkinson worked with Samuel Slater and other local factories, creating custom items to order necessary for the various machinery.

The lower level of Wilkinson Mill houses the reproduction water wheel that powered the entire mill in its heyday. Due to the lack of rain and subsequent low water levels, the wheel wasn’t running during our visit. When it is working, the wheel does not operate at maximum capacity: apparently running even at a minimum the sound is deafening. According to Kathryn, many of the men who worked there did go deaf.

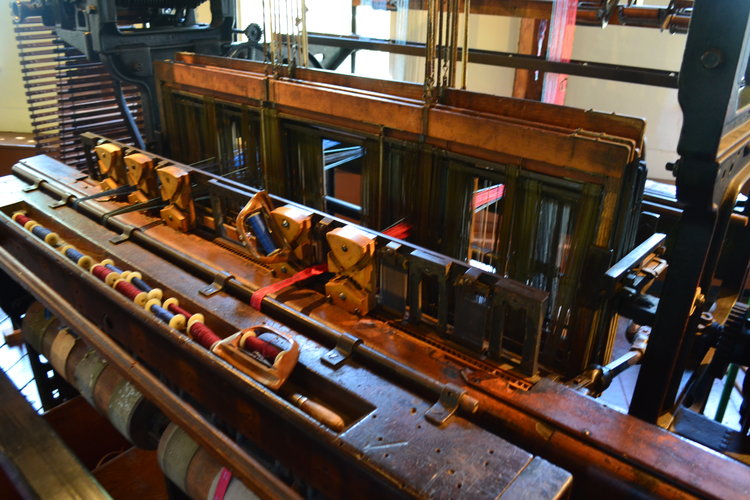

On the second level were various examples of machinery (most of it originals, though not to this particular mill) lining the walls, aisles, and niches throughout the large otherwise open room. Small informative signs were fixed to the majority of the machines, helpfully telling what they were and what sorts of tasks they did.

Belts attached to wheels crisscrossed the ceilings, connecting the various machines to the main shaft rising out of the floor, itself connected to the massive wheel down below. Of course, the wheel itself wasn’t turning, but the modern magic of electricity fixed that problem. With the flip of a few switches, Kathryn had the gears spinning, the belts whirring, and the machines grinding.

She demonstrated the bobbin drill (it drills the central hole in a wooden bobbin) and went over the screw cutter (it was not attached to the power source), detailing how it worked and the care and attention the man operating it had to have. (Fun Fact: My great-grandfather, a die-cutter, had a machine almost exactly like the screw cutter, only his was powered by electricity instead of water.)

Interestingly, all of the workers in this particular mill were skilled men and their younger male apprentices. In order to be hired, each man had to demonstrate he was experienced; in return he was paid the handsome sum of $1 to $2 dollars a day. Compared to the 50 cents a week earned by the boys and girls who worked at Slater Mill, it was both a respectable wage and a respectable job. The job did come with a price, however: “loafing” was not tolerated, even in the case of an accident, and often men would hastily bandage their own injuries in order to return to work as quickly as possible. If fired, a man’s reputation as a “loafer” would spread to all the other mill owners in the area, and he would be forced to leave said area and find work in a different region altogether.

The last building on the tour is Old Slater Mill, though only the first floor is open for public inspection, the upper floors being used as event spaces. Old Slater Mill was the first to use what was dubbed the “Rhode Island System of Manufacture,” in which small, privately owned mills were often managed by the owner himself. Unlike Wilkinson Mill, these operations employed entire families, including women and children. All employees worked long hours in poorly ventilated mills (they thought keeping the windows shut improved the thread produced), filled with the thick dust created from the tiny fibers released into the air, and surrounded with the deafening noise of the machinery.

This building was laid out a bit more like a traditional museum than the other two, with a portrait of Samuel Slater in all his wealth and glory, and a series of displays with small information texts. However, as Slater Mill is set up to be gone through as part of a guided tour, the information is skeletal at best, including the name of the machine, the inventor and date invented, and the acquisition notes.

A series of the machines were discussed in depth; first up is a carding machine secretly invented by Samuel Slater and his business partner in the dead of night (idea theft was a really big problem back then). The one seen here is a reproduction, the original is located in the Smithsonian. (What appears to be a boy in the background of the picture is actually a plastic mannequin representing a child working with a freshly unpacked bale of wool.)

The purpose of these machines, some of which were not used at Slater Mill, was to demonstrate the vast differences between the homespun cloth tradition of most of the eighteenth century (and earlier human history) and the industrial methods that replaced it. Examples included the 1779 Crompton Spinning Mule (a replica from 1930), the ca. 1830 Speeder/Roving Machine, and the ca. 1835 Throstle Spinning Frame.

Now, the Throstle Spinning Frame is from the Locks and Canal Company in Lowell, Massachusetts, who were well known for employing young girls in rather miserable conditions. The machine transferred thread from the large wooden spools seen in three rows on top of the machine down into smaller wooden bobbins below. When the smaller bobbin was full, the girl had to stop the spinning metal piece whirling around it with her bare hands, pull the full bobbin off, cut the thread, stick the bobbin in a basket, and then thread and set a new, empty bobbin in its place. Depending on how quickly the bobbins were filled there would be either one girl per side or one girl working the entire machine.

Kathryn said she has tried stopping the metal spinners before and they hurt her hands, even as an adult woman. She believes it probably hurt a little girl’s hands even more.

The poor conditions that textile workers labored under lead to a brief discussion of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City, and how the growing awareness of the regular mistreatment suffered by those workers lead to an improvement in conditions, hours worked, and wages earned.

Thus the topic of textile industry reform ended the structured part of the tour, but that wasn’t the end of the visit! Apart from the machines that were covered in detail, there were quite a few out on display that were not. We were free to roam around the remainders and ask questions about any particular machines that caught our fancy.

One such object was the 1891 Circular Knitting Machine of the Tompkins Brothers Machine Company in Syracuse, New York, and donated by the same company in 1996. It does pretty much what the name implies, but boy howdy did the finished items look odd hanging from the ceiling like they did – almost like some sort of sea creatures. Kathryn maintained that they were in fact not a form of cephalopod but were used for seamless shirts and skirts, while smaller versions produced socks.

The machinery itself was quite sophisticated, as were most of the others located at the end of the tour. It really emphasized the journey through the textile industry we had gone on, starting with the hand-held carding brushes and the wooden peddle loom and ending with a machine that knitted seamless garments and a monstrous weaving beast that replaced the loom.

It is interesting that the Slater Mill Museum chooses to end there, at the height of its powers, instead of also showing the decline of the textile industry in New England and Old Slater Mill’s passing from operational mill to historic site. In a way it’s rather unfortunate, as it is a part of the site’s history. However, chronicling the ups and downs of the mill industry is not the purpose of Slater Mill: it is the celebration of the journey – the American Journey – from an agrarian culture dependent on the industry of England to an industrial powerhouse in its own right, with Old Slater Mill as the spark that ignited the flame. As this flame Slater Mill chooses to represent itself, and I for one am pleased to see it burning so bright.

Sources:

Rivard, Paul E. “Samuel Slater: Father of American Manufactures.” Meridian Printing: East Greenwich, Rhode Island. 2015.

Slater Mill. “Sylvanus Brown House.” museum sign.

Slater Mill. “The Wilkinson Mill.” museum sign.

Urso, Lori. Email interview by Rachel Polaniec, 19 July 2016.

_Woonsocket.org. “Samuel Slater: Father of the American Industrial Revolution.” Web: Accessed 5 August 2016. http://www.woonsocket.org/slaterhist.h