The Frontier Culture Museum began life as one thing and ended up being something else. What didn’t change is the overall focus: the American people, the exploration of the American identity, and an attempt to help Americans understand who they are, where they came from, and what the frontier experience means in shaping the national character of the United States. The Old World/New World system is modeled after a sister museum located in Northern Ireland, the Ulster American Folk Park (UAFP).

Both museums resulted from the efforts of the late Eric Montgomery (1916-2003) and Henry Glassie. Montgomery was an English Civil Servant in Ireland who spent time in the United States and was interested in America. He sought to create a folk museum for the nation like the one he was making in Northern Ireland, albeit broader in scope. Seeking to explore the origins of the American people, his concern was that Americans are cavalier about the past and don’t fully appreciate where they came from, neglecting their obligations to their ancestors. In 1984, after a lengthy process involving the Virginia General Assembly, the Governor of Virginia, visits to historic farms in England, Northern Ireland, Germany, and Virginia, the British House of Lords, and the raising of lots of private funds, the first historic structures arrived from County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It was followed by an American farm from Botetourt County, Virginia, then a German farm (dedicated by the German Ambassador in October 1991), and a seventeenth century English farmhouse (the dedication being attended by dignitaries from the British Embassy).

In the early 2000s, the necessity of moving away from a Euro-centric notion of American frontier culture and peopling of the colonies came into the forefront, and the need to include a balanced introduction to American Indian influences and culture became apparent. The past fifteen years has seen this implementation: Moving the 1850s American farm to a new location created space for a West African farm, an American Indian exhibit was introduced, a new 1740s American farm deals with the colonial frontier, another American house was included, and several smaller buildings were installed, those being a schoolhouse and a small log church. The change from a folk museum to a history museum came with the new buildings. Now, according to the Museum’s mission statement, this eclectic collection of buildings works together to:

“[I]ncrease the understanding of those cultures which sent significant numbers of seventeenth and eighteenth century immigrants to the backcountry of the Upper South and Middle Atlantic region and of the American culture that resulted from their interaction between 1730 and 1840 which contributed to the westward expansion of this nation beyond Virginia.”

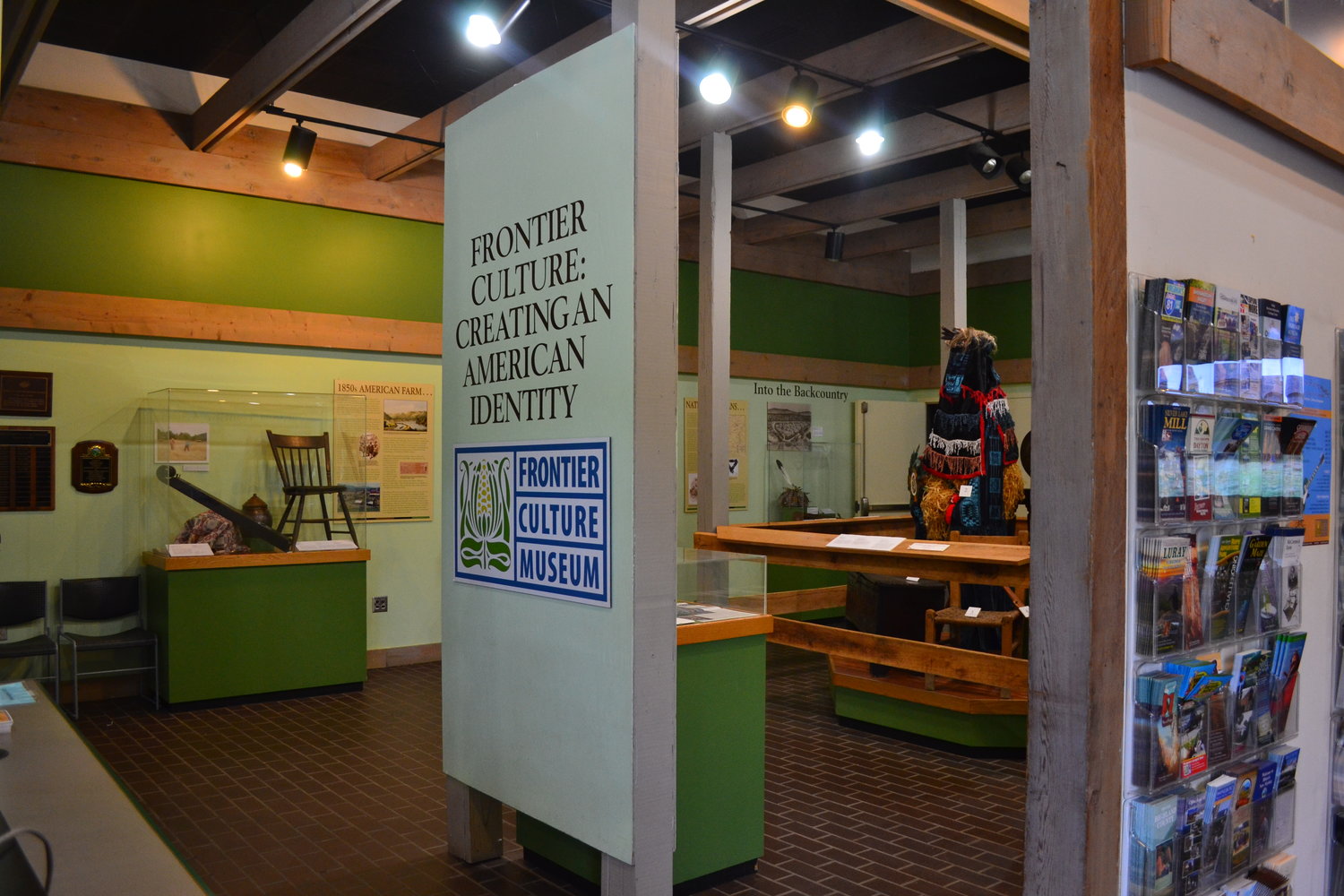

We begin at the Welcome Center, where a small exhibit introduces visitors to the “Origins of American Frontier Culture” using informative wall texts and cases of original objects. If one took the time to read everything available one would enter the site master (or mistress) of the typical German, Irish, English, and West African immigrant, as well as the basic concepts behind the 1850s, 1820s, 1740s, and Native American sites. Or, the Old World arrivals and the New World residents as portrayed by the Frontier Culture Museum. Full disclosure: I did not read all of the texts, but I did look at the objects and read about the ones I found particularly interesting. I am going to assume most other people do the same.

Walking out the back of the Visitor Center one comes to a fork in the gravel path: to the left is the Old World, to the right, the New World. Sort of. There is a lot of walking. A lot of walking. The Old World is located fairly close to the Welcome Center, while the New World is on the other side of the parking lot and Lecture Hall. A shuttle service provides transportation, and there are golf carts available for rent.

I chose to walk, reaching the 1700s West African Farm in respectable time.

The compound consists of four buildings showing how an Igbo family lived in what is now southeastern Nigeria. This family unit was made up of one man, his two wives, and their children. I was able to speak to the staff member on site, who, while not in costume, was very friendly and quite informative. The first house belonged to the man, it was his personal space where he would entertain friends and conduct business.

Other than when cleaning, the women did not have access to his ‘room.’ Each wife also had her own space, the first wife behind his house to the right, the second wife to the left. Spaces for additional wives would be placed behind those of the first and second. In order to take a wife, a man would have to be able to provide her with a house.

The compound includes two kitchens, one for each wife, and a pavilion that staff was in the process of making using the traditional ‘puddling’ technique.

The buildings themselves were not moved from Nigeria; as Eric Bryan noted, “How can you move mud buildings?” The Museum therefore relied on descriptions of pre-colonial accounts and building surveys done by the British in the 1920s. Staff also traveled to Nigeria and saw traditional buildings for themselves. An architect did measured drawings of the ones that looked like what they wanted to recreate, while a man of Igbo origin who had done traditional building techniques when he lived in Nigeria helped with the actual building of the structures on the site. While I was there several employees were ‘puddling’ outside of the compound, mixing clay and water with their bare feet in order to have a workable material with which to create the pavilion. Two young visitors came by and tried their feet; the staff offered helpful advice while their mom worried about the interior of her car (they had a hose available to wash off the clay).

Leaving the West African farm, a cattle pasture came into view, where the Museum keeps cattle. I love cows, so I was very pleased to see them. Cows being cows, they seemed thoroughly unimpressed with me. Especially the one in the background.

The 1600s English farm, however, was very impressive, as it is basically pink. This is due to the way the house was constructed back in seventeenth century Worcestershire. The timber frame was joined using mortise and tendons, creating an interlocking frame of oak; this house uses the common square framing pattern, and the empty spaces were filled in with wattle and daub to form complete walls. Covering the panels with limewash provided the tint to the infill, in this case pink, which blended with the native Worcestershire red sandstone foundation.

I spoke to a trio of costumed young ladies sewing in the front room, the eldest of whom talked about the original family. The house was owned by a wealthy yeoman farmer, or someone who owned at least some of his land but was not a member of the titled aristocracy. This house is the most substantial and prosperous of those in the Old World farm dwellings held at the Museum, though that might be difficult for modern visitors to believe. The home, while large compared to the others, is rather tight by modern standards, the rooms are dark, and the furnishings are nothing more than sparse. This is not an accident, according to Mr. Bryan. It’s important to remember that our modern ideas of furnishings differ from theirs, and that these people are not the gentry – they’re better-off peasant farmers. Hence, the Museum depicts them as such, although it can be confusing to today’s visitor.

The 1700s Irish forge is after the English farm, and while it has a plain white exterior there’s plenty of color within, as a costumed interpreter was hard at work creating hand-forged nails. North American colonies under British rule often faced a shortage of skilled craftsmen, such as blacksmiths. Those colonies fortunate enough to have ties to Northern Ireland’s province of Ulster often recruited blacksmiths and other skilled craftsmen to come to America to provide the services they so desperately needed. This particular forge probably dates to the late eighteenth century, at least four generations of blacksmiths in one family worked here from the early nineteenth century until the end World War II.

Up next is the companion to the Irish Forge, the 1700s Irish Farm. Like the forge, this farm is from eighteenth century Ulster. Ulster was home to Protestant dissenters, many of whom moved to the American colonies with encouragement from the British government. A large number of them immigrated during the eighteenth century, becoming an important group among frontier settlers. Unfortunately the area was closed due to repair work being done on the thatched roof [in 2016], but it did allow for an opportunity to see how thatching is done as part of restoration work so I wasn’t too disappointed.

The 1700s German farm was open to the public, as was its large barn and garden. Like the Protestant dissenters from Northern Ireland, the British government also encouraged German-speaking Protestants from the Rhineland of the then-Holy Roman Empire to settle in the North American colonies. This farm was located in the village of Hördt in the Rhineland-Palatinate from the late seventeenth century through the late twentieth century. Its timber-frame style is typical for homes in the western German states of Palatinate, Baden-Wurttemberg, and Hessen, from where the majority of immigrants to colonial America originated.

The interior decor of the house itself is similar to that of the English home, albeit with a Teutonic twist, while the barn and the garden enliven the German farm’s offerings, with an impressively large barn filled with the strange-looking German spitzhauben, once common barnyard chickens, and now funny poultry with crazy hairdos.

The German farm ends the Old World, and it’s a lovely hike across the site into the New World, complete with a little sign explaining the journey across the Atlantic.

I did like the signage at the Museum, there was one large sign per building/site describing the background, people, farming practices, life, immigration, and contributions to American culture, as well as pictures of costumed interpreters in situ pertaining to each. So if you didn’t take the time to read about it in the Visitor Center you get a second shot once you’re on the actual site. Of course, there were also signs that were purely directional, and they were pretty helpful too.

After the aforementioned long walk past the parking lot and large, modern barn structure that is the Lecture Hall and (I’m assuming) storage facility for the non-period machinery used on the site, I reached the New World.

The first site, fittingly, is the 1700s Ganatastwi, which means “small village” in the language of the Onondaga Iroquois. It represents a displaced native community just beyond the edge of a colonial settlement in the mid-eighteenth century.

The 1740s American farm is similar in feel to that of the Ganatastwi, showing settler life on the raw western edge of Great Britain’s North American empire. While I was there two staff members, one costumed, one not, were in the process of building a fence around the settlement. I believe this is because the Ganatastwi and the 1740s farm are the latest additions to the site and therefore only one has been properly fitted up with adequate signage as of this writing [July 2016]. Both showed potential to match the other ‘farms’ and were obviously being worked on, but they lacked the established feel of the Old World sites and therefore seemed as if they were inferior to the others. Perhaps this was intentional; the nature of these two farms – the displaced American Indians and the household of a settler on the edge of civilization – makes them prime candidates for an unsettled, unestablished atmosphere. I’d be interested to know if they keep that overall feeling or if it’s just an unintended consequence of the actual newness of the site that will give way in subsequent years.

In contrast to the preceding sites, both Old and New, the 1820s and 1850s American farmhouses, the schoolhouse, and a handful of smaller outbuildings and several large barns created a cluster of buildings unlike the spaced-out buildings from before. I believe this too, if intentional, makes sense. The Old World sites are from different countries and are therefore spaced farther apart. The great distance between the Old and New Worlds, again, makes sense. The American Indian village and the 1740s farm also are logical in their comparative isolation. Now as we head into nineteenth century America, an age of increased wealth, trade, travel, and overall accessibility, the rather close proximity of the farms is readily understood. To further emphasize this point, a tinsmith is located near the road, right by the shuttle stop. According to the tinsmith himself, in eighteenth century America two tinsmiths, brothers, arrived from Ireland and settled in Connecticut. There they trained others in the trade, and there the trade stayed in New England until the nineteenth century, when railroads brought them to Virginia and the rest of the country.

My theorizing aside, the first house in the cluster is the 1820s American farm, representing the new type of house built by the next generation of pioneers.

This generation had common experiences, notably the Revolutionary War and the founding of the United States, and began to identify as Americans while losing ethnic differences. The exception to this was the Virginia Germans, who maintained their language and customs up through the 1820s before beginning to adopt the mainstream American lifestyle, an attitude that is reflected in the interior décor of the house.

After the 1820s farmhouse is the American schoolhouse from a rural community dating to 1820-1850. This building was the Shuler School, originally located in a hamlet near East Point in Rockingham County, Virginia. In the mid-1970s it was dismantled and moved to the grounds of Montevideo High School, where it remained until 2007 when it was donated by the Rockingham County Public Schools to the Frontier Culture Museum.

Across the way, past the tin smith and the shuttle stop, is the final house, the 1850s American farm. By this time, Americans lived along North America’s Pacific Coast, vast areas of the country were settled and those that weren’t were rapidly decreasing. These settlers were usually American born whites or enslaved black Americans, as well as some new arrivals from Ireland and the Germanic states.23 New technology and imported goods were available, however many rural farmers chose to retain many of the ways of life from 1800.24 This is visible in the furnishings of the 1850s farm; like its sparsely-furnished neighbor from the 1820s or distant relation in the 1600s English farm, the house is almost Spartan in terms of décor.

Because the Museum is focused on providing as accurate a portrayal of frontier life as possible this is a natural decision, however it does have the drawback of making the house not very interesting, at least not from a stop-and-linger perspective. The presence of costumed interpreters helps, if one will take the time and trouble to talk with them. I found that all of the people I spoke with were engaged and eager to converse, they knew about their craft, about their time period, about their house, and were more than willing to talk about themselves and their experiences working at the site (up to and including personal underthings).

The Frontier Culture Museum tries to understand how the people on the frontier thought, including what they believed were adequate living conditions, their ultimate goal being the accurate and truthful representation of how the people lived, what they had, and how they used it. In doing so, the Museum hopes to educate the public, to allow them to explore what it means to be an American. Being an American wasn’t about having lots of fancy things stuffed into your house. It still isn’t, although admittedly many current Americans seem to have forgotten that. Like the people who make up the Museum, I believe that studying frontier culture and early Americans can help us remember. And, like Mr. Bryan said, he wants visitors to be thinking about America’s origins months after they visit.

At least in my case, the Frontier Culture Museum will have succeeded.

Sources

Eric Bryan, interviewed by Rachel V. Polaniec, July 15, 2016.

Frontier Culture Museum. “1820s American Farm” museum sign.

Frontier Culture Museum. “1850s American Farm” museum sign.

Frontier Culture Museum. “American School House” museum sign.

Frontier Culture Museum. “Visitor Map.”

Museum of American Frontier Culture. “Guidebook.” American Frontier Culture Museum: Staunton, VA, 1997.